At the Olympics, the pressure is obvious.

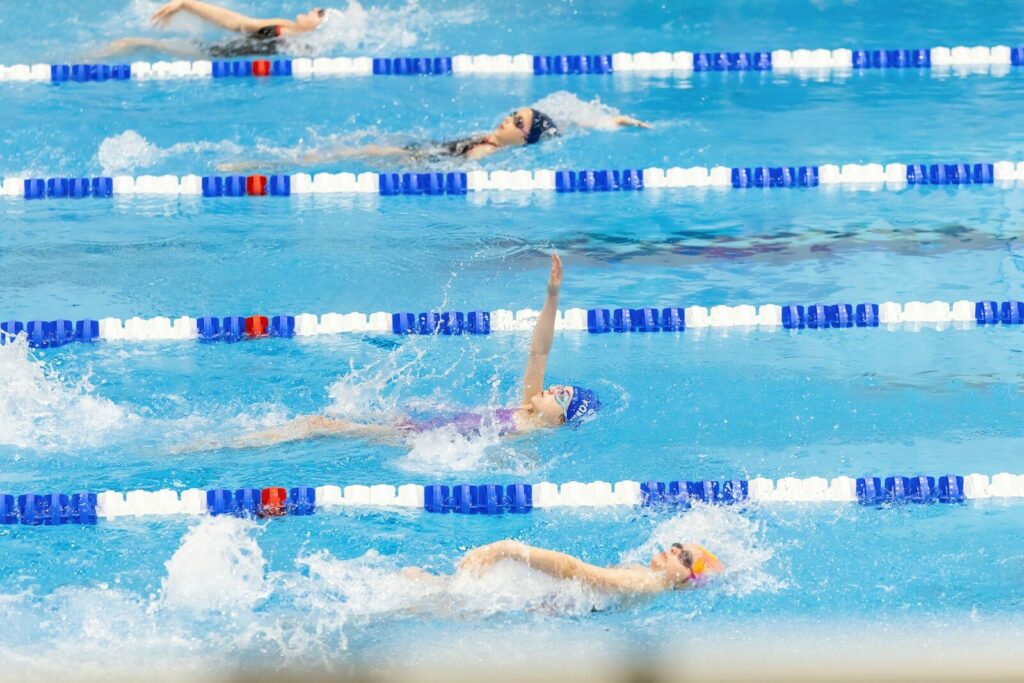

You can see it in the stillness before a gymnast begins. In the tight jaw of a swimmer behind the blocks. In the microsecond before a routine either lands — or doesn’t.

But sports anxiety in kids doesn’t begin on a world stage.

It begins much earlier.

On neighborhood fields.

At weekend tournaments.

In carpools filled with quiet expectations.

The Olympics simply make visible what many young athletes already feel: performance pressure can become deeply personal.

The Olympics Make Pressure Visible

The Olympics are powerful because they compress years of training into one moment. We’ve seen elite athletes step back from competition to protect their mental health – reminding the world that pressure at this level is real.

One routine.

One race.

One shot.

When the margin between gold and silver is a fraction of a second, we see what high-stakes performance looks like under a microscope.

But here’s what often gets missed:

Young athletes are absorbing that intensity.

They’re watching how athletes react to mistakes.

They’re noticing how commentators talk about success.

They’re seeing how the world responds to winning — and to falling short.

Even if no one says it directly, the message can land clearly:

Performance matters. And when performance matters enough, identity can quietly attach to it.

How Sports Anxiety in Kids Actually Develops

Sports anxiety in kids rarely comes from weakness.

It develops when effort, identity, and belonging start to intertwine.

A child loves soccer.

They work hard.

They improve.

Adults praise the dedication. Coaches notice the talent. More time and money get invested. Travel teams begin. Private lessons follow.

Nothing about this is wrong.

But slowly, the stakes rise.

Now performance doesn’t just mean “How did I play?”

It can start to mean:

- Did I justify the investment?

- Did I let my team down?

- Am I still the “good” one?

When performance becomes personal, the nervous system responds accordingly.

A missed shot doesn’t feel like feedback.

It feels like threat.

That’s when anxiety shows up — not because the child is fragile, but because the brain’s stress response is trying to protect something that feels essential.

When Performance Becomes Identity

The shift is subtle.

Instead of:

“I play soccer.”

It becomes:

“I am a soccer player.”

Instead of:

“I had a bad game.”

It becomes:

“I am bad.”

High-achieving kids are especially vulnerable here – particularly in cultures where achievement becomes tightly linked to identity. They’re used to succeeding. They’re praised for it. They internalize it. Patterns like these often persist into adulthood, and understanding perfectionism in adults can shed light on what kids experience today.

The Olympics magnify this dynamic.

We hear stories about athletes who have trained their entire lives for this moment. Commentators talk about legacy. Careers. Redemption.

And young athletes are watching.

They may not consciously think, “My worth depends on my stats.”

But their nervous systems are highly attuned to patterns of approval, attention, and pride.

If belonging feels conditional — even subtly — anxiety will do exactly what it was designed to do.

It will prepare for danger.

Why Youth Sports Feel More Intense Than Ever

Youth sports pressure has changed – and even pediatric experts have raised concerns about early specialization and burnout.

Seasons are longer.

Specialization happens earlier.

Social media amplifies highlight reels.

College recruiting conversations start younger than ever.

Even in loving, supportive families, the culture itself can feel intense.

Kids don’t just want to win.

They want to justify the sacrifice.

They see the money spent. The driving. The scheduling. The missed weekends. And even when parents never say it out loud, many kids feel it:

This matters.

When “this matters” starts to sound like “I matter because of this,” sports anxiety in kids becomes almost inevitable.

What Parents Can Do to Lower Pressure Without Lowering Standards

Reducing anxiety doesn’t mean reducing ambition.

It means separating identity from outcome.

You can:

- Praise effort and decision-making, not just results.

- Talk about mistakes as information, not verdicts.

- Share stories of athletes (including Olympians) who struggled and grew.

- Make it explicit — often — that love and belonging are not tied to performance.

After a game, instead of:

“Why did you miss that?”

Try:

“What felt hardest out there today?”

Instead of analyzing stats first, ask how their body felt. What they noticed. What they learned.

Standards can stay high.

But love has to be bigger than the score.

When kids know that who they are matters more than how they perform, their nervous systems settle. Confidence becomes more stable. Resilience grows.

The goal isn’t to raise a gold medalist.

It’s to raise a human who knows they are more than a moment.